First game players salute the fans opening night of Hartford Jai-Alai’s inaugural season, May 20th, 1976

By Marty Fleischman

During the 1975 Tampa Jai-Alai season, I was tasked with finding and training two announcers for the first season of Hartford Jai-Alai. Since the season would overlap with our other Florida fronton seasons, we could not use any existing personnel. Any new trainees would have to relocate to Connecticut.

While looking for two new candidates, I was still trying to make my big score. I had already learned my lesson that the games were not “fixed” like everyone suspected. Remember how foolish I was when Solaun and Ramon told me they “had” to win the 12th game the previous season? Well, that didn’t work out so well for me. But maybe I could still get some inside information that would pay off big.

One matinee day in late April, I was in the player’s quarters a half hour before the first game. Many times, I would go into the restricted area presumably to get some future entries, but mainly to see Ricky (Solaun). I would always speak to some of the English-speaking players, just to be friendly. One of my favorites was Salazar. He was Basque but spoke great English, along with French and Basque. “Sallie,” as we called him, was struggling to put on his jersey, complaining of a serious sunburn from the beach the previous day. “Martino, I can barely move,” he told me. “I hope I don’t have to scratch.”

Salazar was one of the best players in the early singles game, had been on a win streak, and was undoubtedly going to be the favorite that day. I politely told him that I hoped he felt better and went back to the booth, anxiously awaiting the call from player manager Enrique Beitia.

Beitia would always inform us each performance of any changes to the program so we could make the announcements to the bettors. Beitia called and said, “No scratches today.” Again, this was my chance, I thought.

I mapped out a plan to box the long shots in the game, leaving out the odds-on favorite and severely sunburned Salazar. I found a friend to place the bets. The players marched out onto the court. From the booth, I could see Sallie’s reddish skin above and below his elbow pad.

When Salazar entered the court for his first point, he played like a demon. He ran seven straight points for the win. Apparently, he felt no burn. But I did. My ears were on fire as I lost a week’s pay. It was a good thing I was to train announcers and not the bettors.

I was given another title, World Jai-Alai’s “Corporate Supervisor of Announcing.” That meant, I was to train any new announcers for any of our facilities. Finding two prospective candidates who would move to the northeast was proving to be a challenge. We even put an ad in the newspaper. A few finally responded.

Danny Bazarte and Bill Couch were two students about to graduate from the University of Tampa. Both had been athletes (baseball and wrestling), but neither knew anything about Jai-Alai. But they were eager to learn and moving to Connecticut was not an issue. So, I spent the next few months preparing them for their new adventure.

Meanwhile, there were some interesting developments happening at World Jai-Alai’s corporate headquarters in Miami. John Callahan, the newly appointed CEO, suddenly resigned! In Tampa, we were shocked. He had just taken over the reigns of our company. Hartford was just months from opening. This didn’t make sense.

I later found out that the State of Connecticut Division of Special Revenue, the regulators and licensing bureau, threatened to withhold final approval for the fronton’s license to operate if Callahan was still in charge. Apparently, Callahan, being from Boston, had been seen socializing with some unsavory characters in one of the local bars. The State (I will refer to the regulators with this term) was already suspicious about gambling and was doing everything they could to make it fail in Connecticut. “Callahan has to go or there will be no opening,” the state officials told us.

World Jai-Alai’s executive committee had no choice but to force Callahan to resign. But he did not go quietly. He received a major buy-out that cost the company plenty.

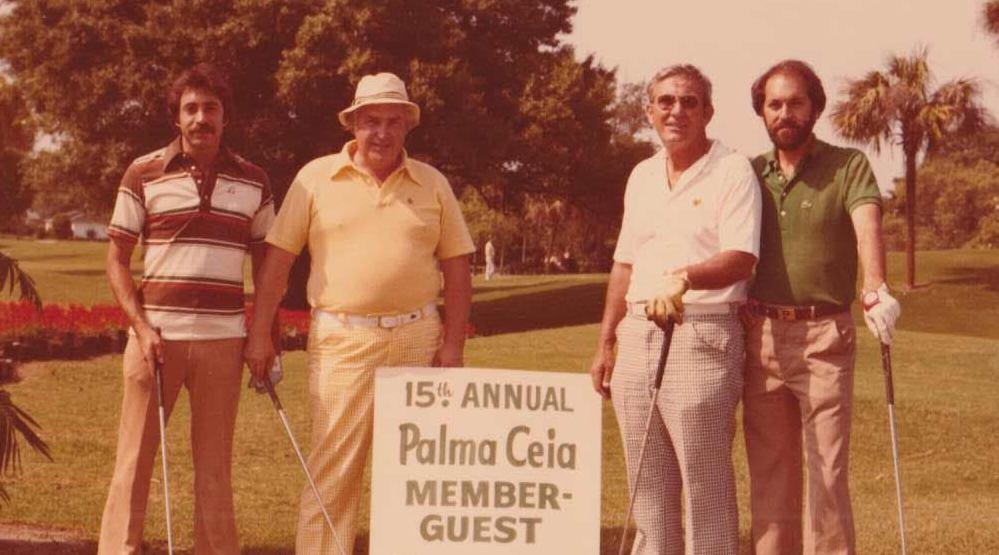

Our new CFO, Richard P. Donovan, whom I had met briefly at that corporate advertising meeting, would assume the role of CEO. Buddy Berenson, the obvious choice to lead the company once again at this very important time, was still in the “penalty box.” The executive committee was only using him sparingly. They still refused to give him any real power or authority, even with Callahan gone. Buddy continued to help the company any way he could, while still trying to mount an offense that would put him back on the throne.

Buddy, son Richard, and I were asked to go up to Hartford prior to opening and help set up different areas of the fronton. Richie was to instruct the box office personnel. I was to set up the announcer’s booth and assist new public relations director Rob Weinberg with preseason publicity. Buddy was to assist new general manager (and rival on the executive committee) Teddy Libby on everything else.

Libby had absolutely zero experience running a Jai-Alai fronton. In fact, he had only seen the game a few times. But his family-owned part of the company. Need I say more? I know Buddy was enduring the ultimate insult being asked to help Libby. Yet, he did it, without complaint. He wanted Jai-Alai to be a success in the northeast. After all, it was still his “baby.”

The weeks prior to Hartford’s opening, the media turned on us. The Hartford Courant ran a series of stories, mostly negative. They opposed gambling coming to their state and definitely showed the editor’s bias. They absolutely wanted us to fail. All pre-opening stories consistently cautioned fans to stay away, that opening night would be a fiasco.

The fronton was located just off I-91. The Courant said the interstate would be jammed, that it would be impossible to get to the facility. Parking would be limited, access impossible. This was ironic because if Jai-Alai were going to be that successful for the Hartford area, it would bring a tremendous economic benefit. But the Hartford Courant was just beginning their campaign against us, I would later find out.

I was standing in the lobby when the doors opened on that opening Thursday night, May 20th, 1976. Buddy, Richie, and I were anxiously awaiting the hordes of Jai-Alai fans anxious to place their first bets. So far, our experience for any new facility was, “If you build it, they will come.” But, on this night, almost no one came!

I went to the announcer’s booth to call the first game. I looked into the 5,000-seat facility and saw just a few hundred patrons. The first game began and there was virtual silence. Not only were there just a few fans, few understood the game. They did not know when and how to cheer. It was very quiet and very depressing. Was this the future for our sport in the northeast?

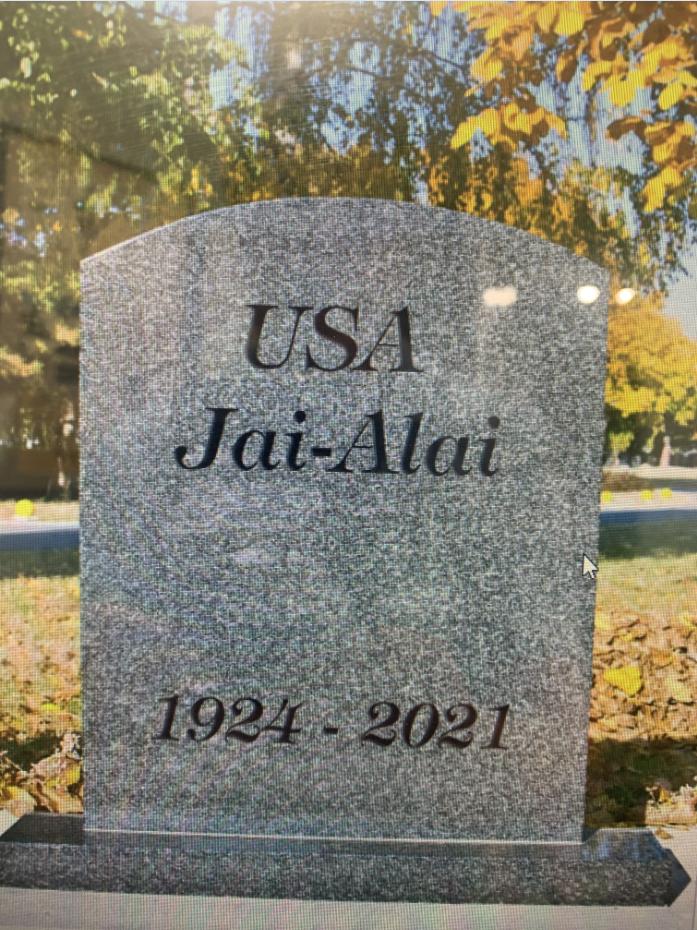

The World Jai-Alai executives were far more depressed than I was. This expansion, if a failure, could bankrupt the company. So far, it looked like a disaster. I-91 was empty. Our parking lot was empty. The Hartford Courant had succeeded in keeping people away. Or had they?