In 1973, Ocala Jai-Alai’s inaugural season was a booming success. Tampa Jai-Alai was on an upward trajectory of record attendance and pari-mutuel handle (betting) mainly due to Buddy Berenson making capital improvements to the facility and bringing in some top tier players, such as Bolivar and Gorrono.

In the ’50s and ’60s, the Tampa Fronton was nothing more than a basic shell of an auditorium. It was dimly lit, had worn seats, and fans saw marginal play on the court. Since the Berenson’s bought it, the fronton was being transformed: new carpeting in the aisles, expanded standing and betting areas on the sides, upgraded closed-circuit televisions, a high-end dining facility, new courtside box seating, and a major upgrade in players.

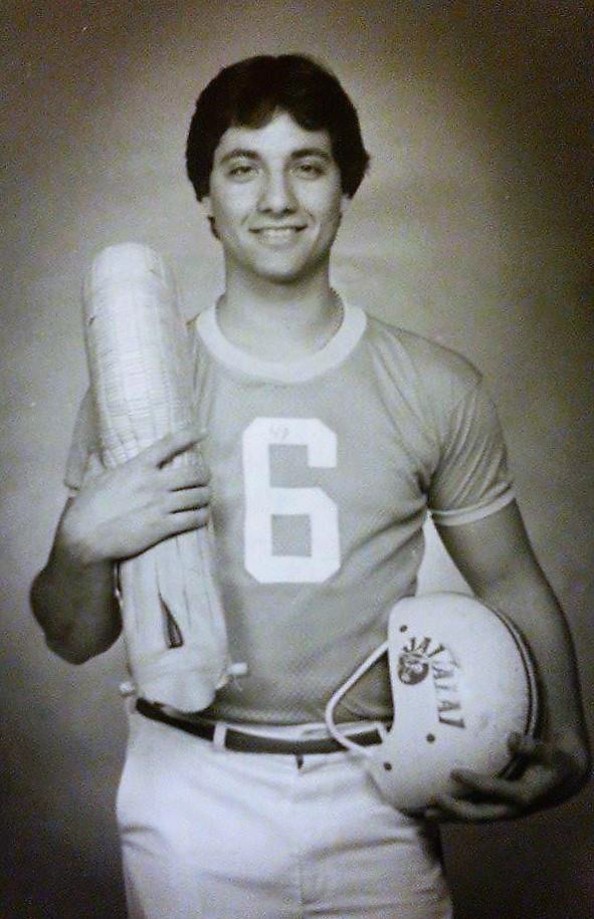

During that second season in Tampa and the first Ocala season, Ricky Solaun and I were getting closer and closer. We came from two completely different backgrounds. He was a Basque, born and raised in a small town in the Pyrenees Mountains of northern Spain, Catholic, high school educated. He became a professional Jai-Alai player in his teens, playing in the Canary Islands, completely on his own. He spoke little English, married a Tampa girl, and was pursuing his dream, playing Jai-Alai in the United States.

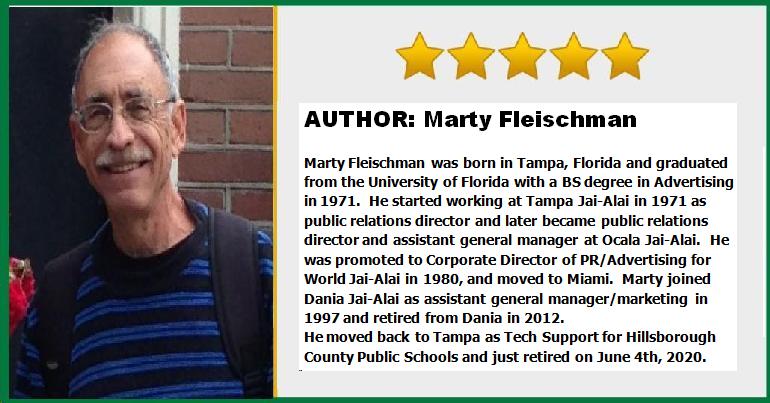

I was born and raised in Tampa, Jewish, graduated from UF, raised in an upper middle class setting, spoke little Spanish and was still living with my mother. Now, I wasn’t George Costanza (Seinfeld fans will know), but it might seem so. My very Jewish mother was always saying, “when are you going to get a real job?” It did sound a lot like George’s mother.

Ricky and I were so different, but a unique friendship was developing, a brotherhood. Somehow fate brought us together, two people from two completely different worlds. We were to face many challenges together. One was soon to come.

Ft. Pierce Jai-Alai was under construction and due to open in the summer of 1974. Our company would have four frontons in Florida, literally dominating the market. But the sport was limited to only Florida. Though Jai-Alai was played in New York, Chicago, and New Orleans in the ’30s and ’40s, it disappeared in all areas of the U.S., except Florida. That was about to change.

Without any warning, the legislature in the state of Connecticut passed a lottery bill in 1972. Somewhere buried in that bill was legalization of dog racing and Jai-Alai. Then, the following year, there were legislative discussions involving a possible “Jai-Alai center in Hartford.” Doubtful they even knew the proper term was “fronton.”

Meanwhile, Buddy Berenson, president of our company, was now facing a once disinterested set of investors on almost every decision. The company’s Executive Committee, consisting of the original Boston investors, was smelling money… and power.

The company had expanded from just Miami Jai-Alai to four profitable frontons, and they became aware of the new Connecticut legislation. The sport could spread further, outside of Florida, perhaps even New York, or California. But expansion required money.

There was talk of taking the company public. This would raise the necessary funds for any possible future expansion and take them off the hook for fronting any further investment.

The Berenson family had brought them this far, with tremendous financial success. Buddy had already shown that he was not only an astute businessman, but he was virtually “The King” of Jai-Alai. The dynasty would continue as his son Richie was learning every phase of the business. Only one thing stood in their way: Alan Trustman and the Executive Committee.

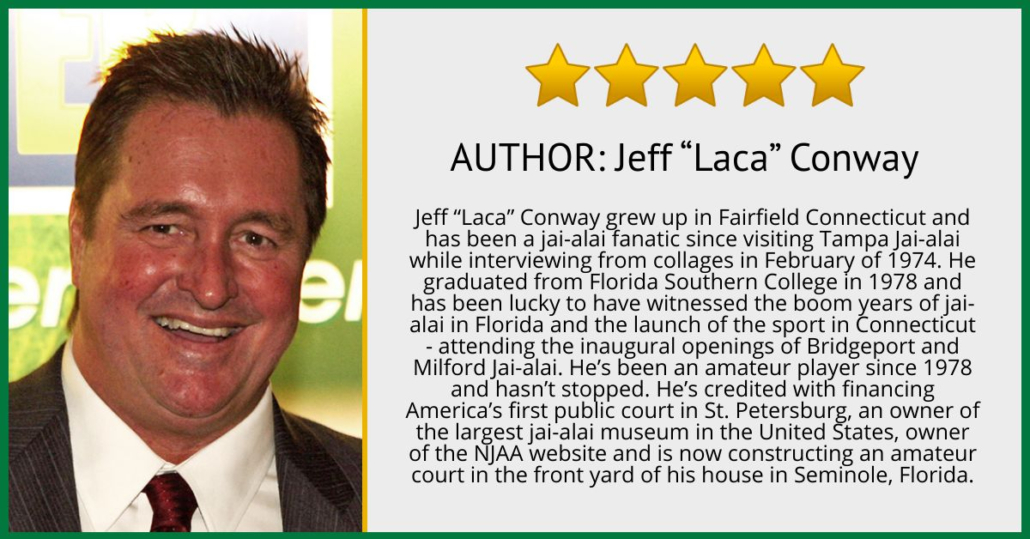

The state of Connecticut did issue three pari-mutuel licenses for three different cities: Hartford, Bridgeport, and Milford. Our company was approved for the Hartford license. Milford and Bridgeport went to two other separate entities. Milford was to be Dania Jai-Alai’s sister fronton.

Meanwhile, in the same year, the MGM Grand Hotel decided to experiment with Jai-Alai in Las Vegas. It was to be used as a gimmick to draw people into their casino. It was not a successful venture and showed that Jai-Alai could not compete with slot machines or table games. (It ended up closing in 1980, a failure as did one in Reno.)

Gossip and speculation were now running rampant in the Jai-Alai industry. This would be the first appearance of our sport in the Northeast, especially in the New York market. Bridgeport was an easy drive from New York City. Some were thinking that exposure in the Northeast could be the launching pad for the sport. There was talk of possible frontons in Chicago and New Jersey. Of course, that required legislation and lobbyists were being hired to make it happen.

In 1973, it was announced that we were now a public company and the new name would be “World Jai-Alai.” The executive committee, consisting of Ben and Alan Trustman, plus the other investors, along with Buddy Berenson, became World Jai-Alai’s Board of Directors.

Then, other new names began appearing, such as Frederick “Rick” Wallace, the new Controller. Soon to join the World Jai-Alai’s corporate structure would be Richard Donovan, Paul Rico, and the infamous John B. Callahan. The battle for control was about to begin. Berenson versus Trustman. The fate of the new Hartford Jai-Alai, the four Florida frontons, and the entire sport was truly at stake. But, in early 1974, the Teamsters Union fired the first shot.