Joey – The Greatest American Player Ever

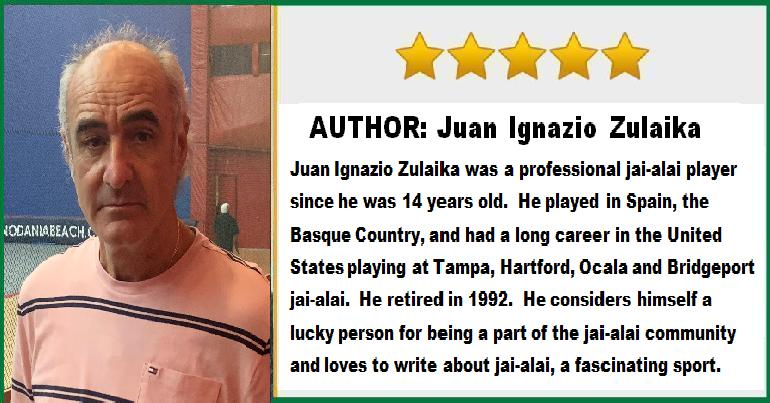

By Juan Ignazio Zulaika

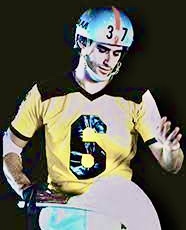

It is complicated to interview a former teammate for whom you feel admiration. A feeling that goes back to a distant time, the year 1980, when we played together at the Miami Jai-Alai, with the number six on our backs. And, without me even touching the ball, he was in charge of winning the quiniela with rebotes and costados.

What a way to play jai-alai!

No wonder that when I left Sheridan Street behind and headed down US-1, I felt butterflies in my stomach, just like that long ago day before jumping onto the court of the legendary South Florida fronton.

We had arranged to meet at noon at the Grampa´s Cafe, an American food restaurant near the Dania Casino-Frontón.

I arrived twenty minutes early after pedaling under a scorching sun, I did it without haste, so as not to break a sweat. The contrast between the temperature outside and inside in such places in Florida is brutal.

When I crossed the threshold of Grampa´s Cafe, a strange feeling came over me. I was going to chat with a native, a living legend of a dead sport in the USA, at least as we have known it.

It was at that very moment that Joey Cornblit entered the Café. The jai-alai player who has made it into the Florida Sports Hall of Fame. Winner of five Tournament of Champions, countless tournaments, and awards throughout his more than twenty years as a professional jai-alai player. The undisputed best American pelotari of all time. For his fans, the best front-courter in jai-alai of the last decades.

He welcomed me with a reassuring smile and with such a friendly attitude that he made me feel at ease from that moment on and during the more than three hours we shared table and tablecloth.

Joey, at 66 years old, looks great, and when he was 49, he almost died of a heart attack while playing golf. He rushed to the hospital without missing a minute and it saved his life. He points to my left arm where you can see the scars from the operations. He has several bypasses inside his body.

I guess that he doesn’t smoke cigars anymore. I remember the Joey of the seventies, smoking his cigars. He tells me no; he still smokes cigars.

“One a day?”, I ask him. “No, I smoke several a day”, he replies.

“What does your doctor say about it?”

“He doesn’t know anything”, he answers me with a mischievous smile.

He likes to smoke cigars especially when he plays golf. A sport he is hooked on. Thanks, in part, to his smoking habit. —“the best are the Nicaraguan ones, from the Fernandez house” — he has an excellent job from which he is not thinking of retiring for the moment.

A few years after leaving jai-alai —he was out of work— he was smoking a “Fernandez” in a cigar-lounge (a place where they sell a lot of cigars of different brands, and you can have a drink). A man approached him asking if he was Joey, the former jai-alai star from Miami. The man could not believe his eyes. He had his idol from the golden years of Miami Jai-Alai in front of him.

The next day he was working for that gentleman, owner of a large company. “The sky opened up for me” he confesses.

“How did an American Jew like you end up in a sport like jai-alai” , I ask him out of the blue. The question intrigues me.

“When I was nine months old, my parents moved from Canada to Miami. My father, born in Poland, was a Holocaust survivor. One of 800 children boarded a train bound for Auschwitz, who miraculously saved his life.

He later fought in the Israeli War of Independence in the secret services alongside Moshe Dayan. My parents emigrated to America and we finally settled in Miami”.

His father, a metal worker, went to Miami Jai-Alai frequently. He liked the Basque sport so much that one day he went to canchitas in North Miami to practice. It was then that Joey, twelve years old, came into contact with jai-alai. Howie, the owner of the courts, sponsored him and accompanied him everywhere he went. He became his best friend to this day.

Six months later, Miami Jai-Alai opened a school to promote the sport and use it as a breeding ground to attract American players and bring them into the roster.

Epifanio, a former professional in the Havana-Madrid fronton, a ball-maker at Miami, became the school’s teacher.

Epifanio, a man who did not raise his voice and gave a lot of explanations to his students, became a sort of father to Joey. The fact that Epifanio and his wife had no children would help the young American become his adopted son.

“If a revolver has six bullets why use only one”, the teacher insisted over and over again.

He implied that a pelotari has to have “all the tools. Knowing how to handle all kinds of jugadas”.

For Epifanio, Joey was his adopted son, but he was also stern with the disciple.

On one occasion, Joey scooped, a bad entrance. Epifanio called him to attention. On the next play, again, another bote-pronto. The teacher kicked him off the court.

El maestro instilled in him a winning mentality. A style of play that would be decisive in his career. Finish the play. “Go for it”. A command of the side so perfect that it would be part of his DNA until he retired.

At the age of 15, in 1970, he went to Saint-Jean-de-Luz (a Basque town in France) to play in the amateur world championship. The American expedition was made up of his father, Piston as coach, his teammates Nickerson and Charlie Hernandez. Marty Fleischman was part of the party and Larsen, manager of the Tampa fronton.

In San Juan, de Luz he met the player who a year later would become his great rival: Katxin Uriarte. Azpiri, Mirapeix II, the Mexicans Zubikarai and Hamui…

There was a French front-courter, Boutineau, who played with his left hand. That was strange and dangerous. They finished third and with the bronze medal he returned to Miami. Not for long.

Joey combined his high school studies with essays at the fronton.

“I was not a good student. I think my father realized that and that’s why he didn’t stop me from dedicating so many hours to the fronton”.

At the age of 16 he made his debut in Miami Jai-Alai, but before that he made his debut in Gernika, during the summer. He remembers when he arrived in Sondika and was met at the airport by Bilbao, the player-manager of the fronton of Gernika. The trip to Gernika by car… He had never seen mountains, the gray color and the rain before. He was overcome with sadness and without speaking Spanish he stayed at Arrien´s, at first in a room without shower or bath, until Castor Arrien took pity on him and gave him a room with more comforts. He spoke by phone on Sundays with his family. His desire to learn and succeed made up for all the hardships.

Debuting in Miami was a dream come true. It was in the 71-72 season, and he did it with other debutantes such as Uriarte (Katxín), Camy, Remen and Gondra.

He started playing the early games and remembers that he won the first one at number two with Arratibel as back-courter. His progression was so rapid that by the end of the season he was playing the medium quinielas.

In the summer of 1972, the Ocala fronton opened. Joey was part of the roster along with the rest of the pelotaris who came from the Tampa fronton. He faced great rivals such as Bolivar, Elorrio, Aramayo II, Pablo… and won all three titles. Most wins, doubles and singles.

That season they played a twelve-set partido between Bolivar-Gorroño and Joey-Laca. The final score was 12 to 11 in favor of Bolivar-Gorroño. Alfredo García, the center judge who would later become Miami’s intendente, commented that he had never seen jai-alai play like that before.

Joey’s second season in Miami was somewhat convulsive. Not all the pelotaris were happy that an American Jew was threatening to get on their nerves.

In the practices prior to the start of the season, one or two opponents made gestures of disapproval at having to practice with the young American. Joey, however, took it as an encouragement to get out on the court and talk his game.

Joey and Uriarte started playing late games from the beginning of the season.

The dislike of Joey rose in intensity when some soulless cadre painted pro-Hitler phrases and swastika drawings on the Jewish-American pelotari’s locker.

Richard “Buddy” Berenson, the owner of the fronton, also Jewish, flew into a rage when he went down to the locker room and saw what had been done to Joey’s locker.

Maestro Epifanio instilled in him the aggressive, finishing game.

“I became so confident in my costado that I didn’t care who my opponent was, and I didn’t care that he was there, waiting for the play. Go for it! I thought. I knew my hit percentage was 70 to 80 percent. That figure gave me a lot of confidence”.

I asked him if he was the only player with those characteristics. He answered no, there were two others of that style: Zulaica and Cacharritos Alberdi.

The best pelotari in singles, without discussion, was Asis. “On three occasions I was the winner in singles. I don’t know how it happened. Asís must have had some mistake on those three occasions”, he tells me smiling.

In doubles, those first seasons in the mythical fronton, Uriarte was his great rival. He thinks better of it and recognizes that the line-up of top players in the front squares was incredible.

Juaristi, Assisi, Mendi, Zulaica, Alberdi… as a dozen of outstanding pelotaris like Gernica II (Beascoechea II), Juan (Elejabarrieta II) or Rufino, Oregui, were all hoping and praying to get into the twelve, the star game.

In 1977 he played three summer months in Euskal Herria. He thinks he did well. He faced Uriarte, Chiquito de Bolivar, Ondarrés, Egurbide.

He has good memories of Churruca. “He behaved wonderfully”. Giving him advice on how to breathe during matches, stretching exercises. Very kind to Linda, his wife, who didn’t speak a word of Spanish. “He instilled in me a lot that you had to practice the same way as if you would be playing a partido. With a lot of intensity.”

Joey doesn’t believe there is a distinction between pelotaris more likely to excel in partidos than in quinielas or vice versa.

«Whoever plays, plays, whether in quinielas or partido matches.»

In the 1970’s, in Florida, Joey had some heated encounters with Bolivar, in 20-score matches. If he remembers correctly, he won them all.

“I think Bolivar played under a lot of pressure. He was the superstar and an American like me was threatening his prestige. The mental part, in any sport, is very important. I think that’s where the key was for me to beat him everytime, we faced each other.”

His favorite back-courters were Soroa, Arratibel and Laca.

His best seasons were from ’76 to ’78.

He also played in Hartford for three seasons, being part of roster that included the best pelotaris of the time.

Joey hoped to retire in Miami Jai-Alai, the Yankee Stadium of the frontons. However, things went wrong when he decided to become an entrepreneur and open a fronton in Phoenix (Arizona). Together with several partners, he raised one million dollars and launched his project in Arizona, inside an Indian reservation.

The Arizona venture did not go forward because the state attorney general objected to allowing jai-alai gambling on the Indian reservation. The appeal to the Supreme Court would have cost them another million dollars.

Joey´s dream was to own a jai-alai.

It is unpredictable to predict what the fronton in Arizona would have meant for the future of jai-alai.

Joey had negotiated with Miami Jai-Alai for a $25,000 annual bonus. Richard Donovan, general manager of the fronton, withheld $50,000 for two years. The retaliation to the Arizona project meant that Joey left World Jai-Alai in 1986 and signed a contract with the competition: Dania Jai-Alai.

In 1986, Joey joined Dania’s roster. The beginnings were not the desired ones. He was uncomfortable. A strange feeling came over him. He had left behind Miami Jai-Alai, a fronton that meant so much to him. The Berenson family had given him the opportunity to play at the legendary fronton and stand out against top-notch opponents. Suddenly he was out of his natural habitat. Everything was strange.

His opponents in the front were fearsome in Dania as well. He could not relax against opponents like Juaristi, whom he was facing again; Zavala, Azca… Elorza at the back, the competition was fierce.

Fernando Orbea, the intendente, encouraged him every time they met in the latter’s office while smoking a cigar.

I ask him about 1988, the year that started the strike that lasted three years. I tell him that if he doesn’t feel like talking about it, that’s fine. We move on to the next point.

The situation is a bit rock and roll. Joey kept playing, he didn’t go along with the strike. I, for one, did go along with it in Bridgeport. It’s been 33 years, enough time to put the ghosts of the past aside. I bring my homework from home; in case we have to bring up the subject.

“There’s no problem talking about it” , he tells me with a tone of assurance.

I let him elaborate.

“It was unfortunate. For my part there was no problem in asking for improvements. What’s more, it’s in the human being to try to improve, to earn more money. However, things were done in an extremely radical way. It was all or nothing. It was not the head that was used, but the guts. Also, there was no respect. If you want to strike, ok, but respect my position. Nothing like that happened. The owners were very rich, except for Berenson, they didn’t love jai-alai. They didn’t mind closing the fronton if it had to be closed. You (Basque pelotaris) could go to the Basque Country and continue playing. I had to stay here. It was unfortunate because we all loved jai-alai”.

At that time, 1988, Joey was earning about $100,000 a year playing jai-alai.

The last two years for Joey were not the most desirable. Several injuries and the occasional operation prevented him from maintaining his level of play.

He retired in 1995. The transition was not easy for him. While he was playing everyone told him: “when you stop playing, don’t worry, I will give you a job. Nothing like that happened”.

When the pelotari stops playing, the situation changes. Having to look for a job. Adapting to a schedule. Other demands. Without the freedom of the professional athlete. Greater, perhaps, for someone who is dedicated to jai-alai.

After working for a security company, he found himself without a job. He went to a cigar lounge and the encounter with a person changed his life. The owner of a large company offered him a job immediately. To this day, at the age of 66, he is about to start collecting his full retirement pension. And to continue working in something that he enjoys, does not cause him any stress, and allows him to play golf, a sport he is passionate about.

He lives in Plantation, near Dania, with his wife Linda. They have two children, Josh and Nicole, and four grandchildren.

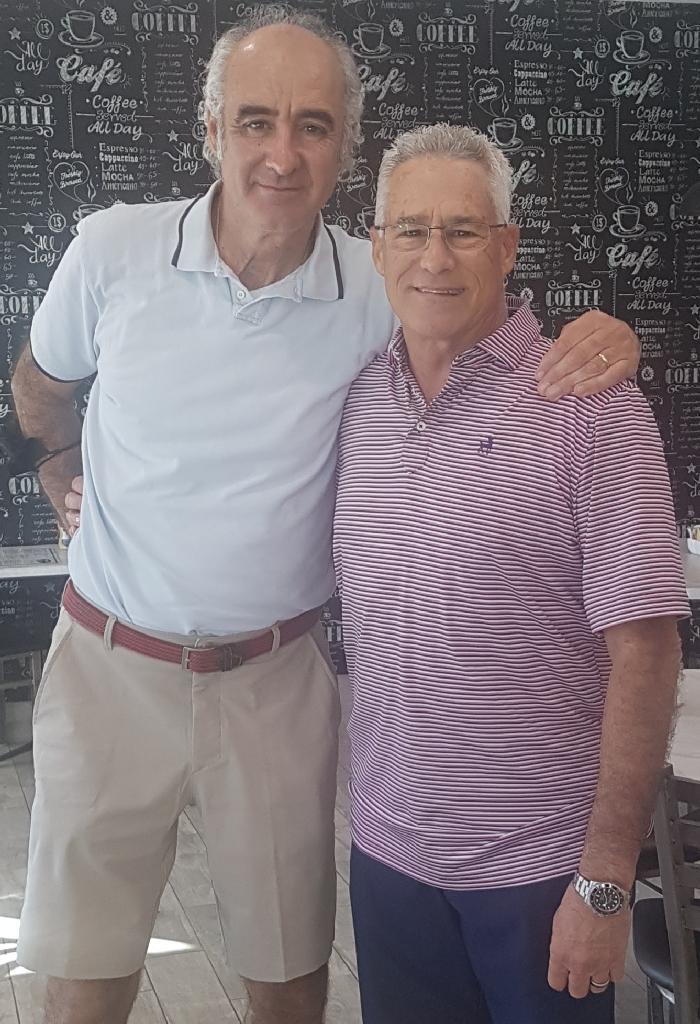

It’s been about three hours. The time has flown by. Joey is a pleasant and attentive person. I have a feeling, as I say goodbye to him and pedal down US-1 in the blazing sun, that I might have been able to get something out of the interview. After all, I had in front of me a living legend for whom I had felt admiration for many years, when I saw him play at Yankee Stadium in the jai-alai. And, more so when we paired up and he gave a masterful pelota lesson.

Before saying goodbye, I search the walls for a photograph of Joey, with a dedication, of which I had been told. I can’t find it. The waitress doesn’t know anything. It’s been a year since the owners changed at Grampa´s Cafe. I ask the waitress to take a picture of the two of us. I want a testimony of the evening.