One Jai-Alai Player Shows Extraordinary Courage

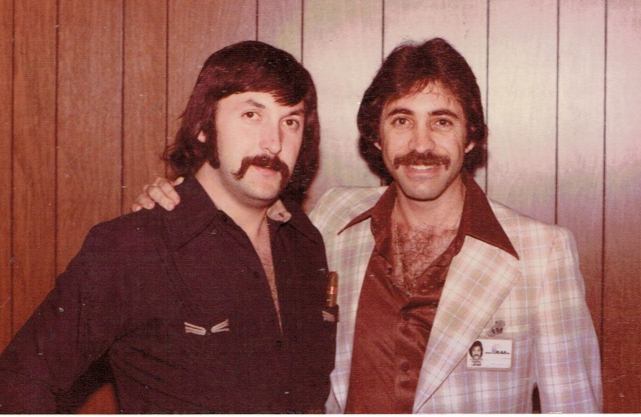

Ricky Solaun (left) showed bravery and fearlessness

on and off the court. I’m proud to be his brother.

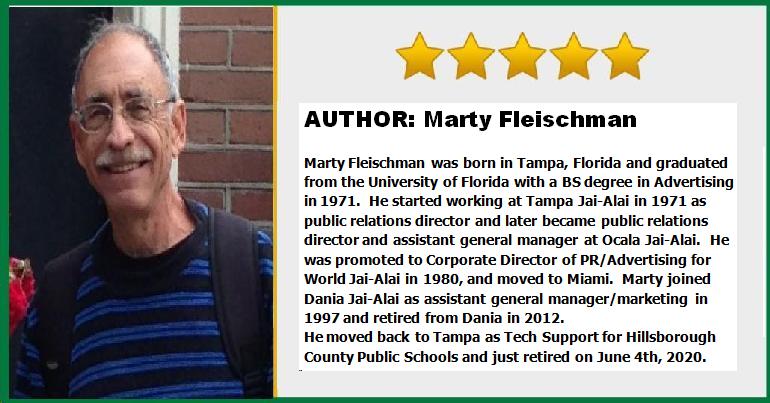

By Marty Fleischman

Sitting in the general manager’s office at Tampa Jai-Alai was always a little stressful. But, on this day, I was not listening to Ernie Larsen’s diatribe of epithets but awaiting the new “Big Three” from our corporate office. Buddy Berenson, President, Rick Wallace, Chief Operating Officer, and John Callahan, CEO, were due to arrive any minute. And I was about to be an integral part of a meeting between these executives and the Tampa players that could change the sport of Jai-Alai forever.

Three days earlier, I asked Ricky Solaun to bring some of the players to my apartment for a meeting. Ricky convinced Laca, Arambarri, and a few others to come over and discuss the impending vote on whether the Tampa players would join the Teamsters Union. Yes, the union of Jimmy Hoffa, the group mostly comprised of truckers throughout the country, had approached the Miami players about unionizing and had received a very positive response. If the Tampa players followed along, certification for all the players in the state frontons would be imminent. That would mean the owners would have to bargain with the Teamsters over player contracts, prize money, working conditions, etc.

The Jai-Alai players had never been represented by a U.S. labor union. In the past, players had joined a union in Spain called Montepio. That union had called a player strike in 1968, where the players remained in Spain instead of returning for the opening seasons of their respective frontons. The owners in the U.S. hired other young players to replace them. Most never returned to the United States to play again, except for some of the stars that signed in Bridgeport, Connecticut in the late ’70s.

Rick Wallace was a young, newly hired accountant that had quickly risen to a top position in our evolving company. Knowing I was close to the Tampa players, he had reached out to me about the approaching union vote.

“We don’t want to deal with a union,” he had told me, “and especially the Teamsters Union… they know nothing about a sports team.” He asked me if I was aware of the players’ complaints and issues. “Our company is changing and if we can address their issues WITHOUT a union, it will be better for everyone,” he said.

By now, Ricky and I had developed a deep friendship. We had already lived together in Ocala and, without question, trusted each other. When I told him, I had talked to Wallace and it might be possible for us to solve the issues without a union, he was very skeptical. “If we complain to the company, we will lose our contracts or be sent back to Spain,” he told me. “We think the only answer is a Player Association or a union. No one wants to take a chance on being sent back,” he said in his improving English.

At the meeting in my apartment, I found the two things that were most important to the majority of players: player prize money needed to be increased and the discretionary bonuses they received at the end of the season should be decided strictly on performance.

In the early ’70s, a player only received $15 to win, $10 for second, and $6 for finishing third. This was supposed to be an incentive for a player to play his heart out. But, in reality, it was truly a small amount of money, even in those days.

There were some discussions on their dissatisfaction with future contracts. They usually weren’t offered to the players until the last day of the season. Also, they wanted better insurance coverage that included their families. But that was about it.

I asked them if I was able to get the company to address these issues, would they consider giving them a chance without the Teamsters Union. They thought most of the players would agree. Fearing repercussions, no one wanted to be the “spokesman” for the players when the Miami executives came for the player meeting.

After the players left, I told Ricky he had to be the one. I was sure that the players would feel intimidated and not want to speak at the meeting. He vehemently said “NO!” He said, “Martino (my Spanish nickname), I am married, I need this job. What else am I going to do if they get mad and don’t give me another contract?”

I promised him that wouldn’t happen. I told him to trust me. If no player speaks up, he had to be the one. Too much was at stake. I believed that our top executives did want to work something out, that it would, indeed, be easier to negotiate directly with the players than with a union.

But they needed to hear exactly what the players wanted. Ricky might be the only one that would have the courage to talk. Even if he was nervous about his English, he could get someone to translate. And that is exactly what happened.

When Berenson, Wallace, and Callahan returned to the front office following the meeting, I asked what happened. Rick Wallace told me, after introducing themselves, they asked about complaints, issues they had with the company. No one spoke. They asked again. Still silence.

Then, Callahan said to me, “A round faced player with a Basque nose and mustache stood up, asked someone to translate because his English was bad, and said that he was speaking for himself, not anyone else. He talked about the issues you told us about. Other players were telling him to ask us things, but he ignored them and spoke directly to us.” Callahan told Solaun that he thought his requests were reasonable and to give them a few minutes to meet back in the front office.

I smiled. I was so proud of Ricky. He showed such extraordinary courage. The meeting would have been a complete failure. These players will face a rock-hard ball coming at them at 180 m.p.h. rather than face three suited Jai-Alai executives. But Jose Ricardo Solaun spoke, with all eyes in the locker room squarely on the young, round-faced Basque. He spoke and they listened.

The company offered significantly higher prize money. The bonuses became based on their season statistics. Better insurance was offered for the families. And the Tampa roster decided to vote down the Teamsters Union.

The players would negotiate directly with the company from that date until April of 1988, when the UAW tried to organize the sport triggering the longest sports strike in U.S. history. That strike spelled the beginning of the end for the sport of Jai-Alai.

I often wonder… did we actually do a good thing for the sport that day? Or did we just delay the inevitable. But, the next 14 years were the most memorable years of my life, filled with extreme happiness and challenging disasters.