Tourney Ends, Job Begins (12 of 91)

By Marty Fleischman

Joey Cornblit’s parents immigrated from Israel to Montreal. They soon moved to the warmth of Miami, shortly after Joey was born.

Charlie Hernandez’s parents immigrated from Cuba to Miami to search for the American dream. They were now living it. The Hernandez’s had traveled to France to watch their son play in the World Olympics for the sport of Jai-Alai. But, would they?

As the entire U.S. contingent, still feeling the exhilaration of the win by Kirby and Nick over the French team the night before, met for coffee and croissants the next morning, you could see trouble was brewing. In fact, it was already brewed. Rudy Hernandez, Charlie’s father, was threatening Piston from withdrawing his son from the tournament to an actual lawsuit against the U.S. Amateur Association. After two matches, his son Charlie was still on the bench.

You could see the pain on Piston’s face. Having never won a single match in past world competitions, the Americans were now 2-0. But he knew it was only fair to give Joey and Charlie their shot against the talented Spanish team of Uriarte and Mirapege. Still, what if this costs the team a gold medal?

Uriarte (played under the name Cachin later in his pro career) was the top amateur player in Europe and was certain to get a future contract in the U.S. (probably Miami). Mirapege was one of two brothers who played for Spain. He was the top backcourter, who would have had a phenomenal professional career, but for the fact his parents emphasized going to college. He was one of those rare athletes that would always remain an amateur.

The decision was made. Joey and Charlie would face Spain. Kirby and Nick would head to the bench. We all ordered more French coffee and extra croissants as it appeared harmony was once again restored with Piston’s decision.

Joey, being only 15 years-old, was cool and relaxed, at least outwardly. Charlie warmed up prior to the match with his parents cheering from our section. Understandably, they were extremely nervous as the four players did the traditional march out prior to the start of the 35-point, head to head partido.

Joey and Charlie had trained under the tutelage of Epifanio, the amazing Jai-Alai instructor at North Miami. Joey, not particularly overpowering in the frontcourt, had perfect form on his right side (forehand) and reverse (backhand). You barely heard the ball strike the cesta as he made a catch, signifying almost flawless style. But Joey’s major asset was this amazing backhand two-wall shot known as a “remate” or “costado.”

When most frontcourters in the sport catch a ball on their reverse, they merely throw it deep to the backcourt, a more defensive shot. But Epifanio trained Joey to throw this sharp breaking two-wall remate that hit the side wall, front wall, and the edge of the court shooting straight to the screen. The shot was almost unreturnable. Joey could score nearly at will while catching the ball on his reverse.

Charlie, being a young, slim backcourt amateur did not possess much power, but was extremely consistent. His job was to catch the deep balls and try to throw it beyond the awaiting opposing frontcourter, keeping them on the defense. His hope was for Joey to be able to catch one in the front and put them away with his remate.

Joey had another major asset. Having trained on the short Miami Amateur court where many balls rebounded off the back wall, he developed a fantastic “rebote” shot… a ball that comes off the back wall. He rarely missed those and placed it in such a way that it became an offensive shot, too.

So, the partido began… this long, physically challenging 35-point match. Joey and Charlie were smooth and patient. Uriarte and Mirapege were throwing all their shots, moving on the court with familiarity and ease. But our team stayed with them, as Joey amazed the French aficionados with his remate, scoring time after time.

But it soon became obvious that Charlie’s consistency would not erase his weak throws. The Spanish team would take advantage of it and keep the ball deep, away from Joey. Where Nickerson’s power and awkward throws were an advantage, Charlie’s throws were predictable and began to cost the American duo.

The partido ended with a 35-33 win for the Spanish team in what was a gutsy, hard fought loss for us. Joey and Charlie had nothing to be ashamed of, they fought their hearts out. They lost the match, but the youngsters won the respect of all the fans that night. After all, they actually lost by only two points to the best team in the world.

In the end, the U.S. team took home 3rd place, a bronze medal as Spain won gold and France took silver. It was the first medal a United States team ever won in world competition for the sport, and we were all very proud.

At breakfast the morning after the conclusion of the competition, Katie Harrington representing Dania Jai-Alai pulled out a professional contract an offered it to Kirby. He signed it quickly with us all proudly witnessing the event. Remember, at that time, very few Americans were playing professional Jai-Alai. Joey was too young and had to wait. Nick was looking for his next wave to surf in Daytona.

Shortly after returning to Miami, Joey, now 16, was in Buddy Berenson’s office accompanied by his parents. He was offered his first pro contract, while still attending Carol City High School. He was too young to sign it without his parent’s co-signing. (I will be discussing Joey’s career in more detail in later articles, as he was one of the most important and impactful figures in the sport).

Nick Nickerson did make it back home to the U.S. and subsequently played at his home fronton of Daytona Beach. Charlie Hernandez would get a chance to play for World Jai-Alai in later years.

Upon my return home, I still had no actual job until December when I would actually do my first pre-season prep. I took the film footage over to WTVT and gave my Dad back that heavy Bell and Howell camera. He edited the footage and had me on, as promised, narrating the grainy, sometimes out of focus, black and white footage of our victories and defeats in St. Jean-de-Luz. It, indeed, was great publicity for Tampa Jai-Alai and the entire sport. I’m sure Ernie Larsen was glad I did not include any footage of La Palanca.

I spent the next few weeks playing amateur Jai-Alai in the mornings at the fronton. Since I had no money, my mother was nice enough to let me live with her in her apartment near West Shore. I was like George Costanza, no money, no job, and living with my mother.

But life was great. Ernie told me my first duty was to sell the program ads starting in September. He told me this would carry me through without a paycheck until the end of December. But he didn’t tell me that I wouldn’t get the 20% commission check until after the season started. So, I was still pretty broke all those months.

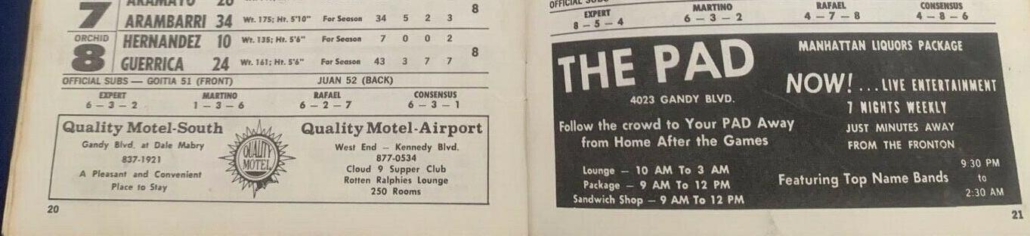

I absolutely hated selling anything, especially advertising. It just seemed difficult to measure whether an ad under the game lineup in the program actually delivered customers to the advertiser. But Ernie told me as an incentive, I could tell buyers that they got on our VIP ticket list for two free seats any performance for the season. So, I pushed that as the bonus worth more than the cost of the ad.

My first call and “sale” went to one of my best friends, my college roommate Bob Cohn, who had opened up “The Cheese Shop” on S. Dale Mabry. I still owe him big-time because he said, “Flash, for you I’ll buy an ad.”

I knew Bob had just opened and was struggling. This was before wine, and cheese was a big deal. But he bought one without hesitation. I designed the hokiest ad with a graphic of a piece of Swiss Cheese that looked like a mouse had taken a bite. And I told him we could do it in “reverse,” making it black on white so it would stand out. I was an advertising genius. Bob probably lost business from that ad.

But, with a sale under my hat, I was on my way. I could not wait to write my first feature story on a player for the Tampa Tribune. I certainly did not know what awaited me the first time I brought one to the revered, renowned, Sports Editor of the Tampa Tribune, Tom McEwen. But, when I left there, I felt like I should look for a new job.